For a long time, I couldn’t grasp what “attention” really was.

Most explanations just threw formulas at me or repeated vague phrases like “compute query, key, and value with a feedforward net.”

But I wanted something deeper. Not just what happens — but why it works.

I’m not ashamed to admit I’m an integrator. I code systems, not train models from scratch. And like many developers I met on forums, I had naive theories like: maybe GPT is just an expert system querying a giant database.

Then I bought Sebastian Raschka’s book Build a Large Language Model from Scratch and finally — finally! — got the answer I was looking for.

Let’s Start with a Puzzle

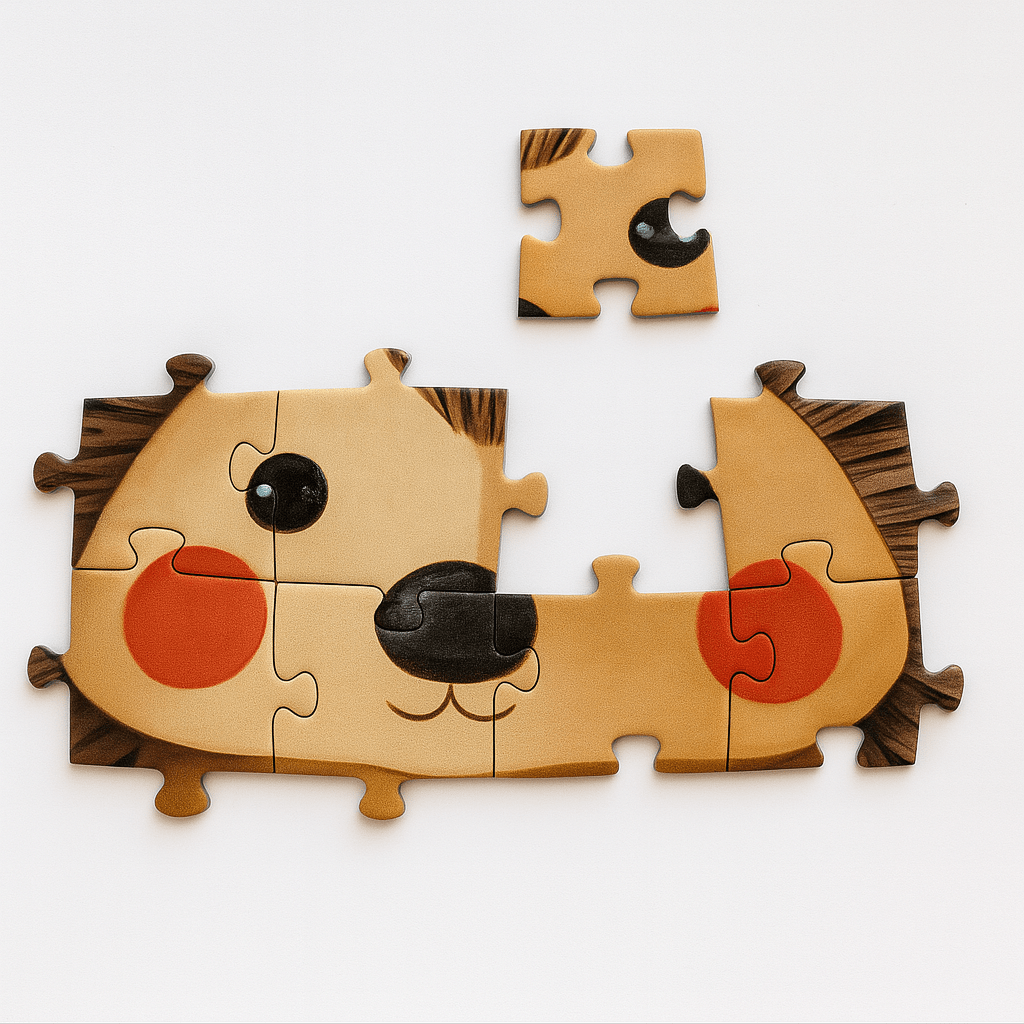

Imagine we have a large 2D puzzle, and we remove some pieces.

The question is: can we guess what’s missing just by looking at the surrounding ones?

If a hole is surrounded by 🌊 blue waves, the missing piece is likely more ocean.

If we see 🐫 camel fur, it might be a hump.

If it’s 🌼 daisies, maybe a flower or a bee.

To illustrate the association visually, I bought a real puzzle and chose one with a variety of details — I picked an adorable hedgehog.

Now let’s think: could we somehow gather information about the face to predict that the missing piece should be an eye?

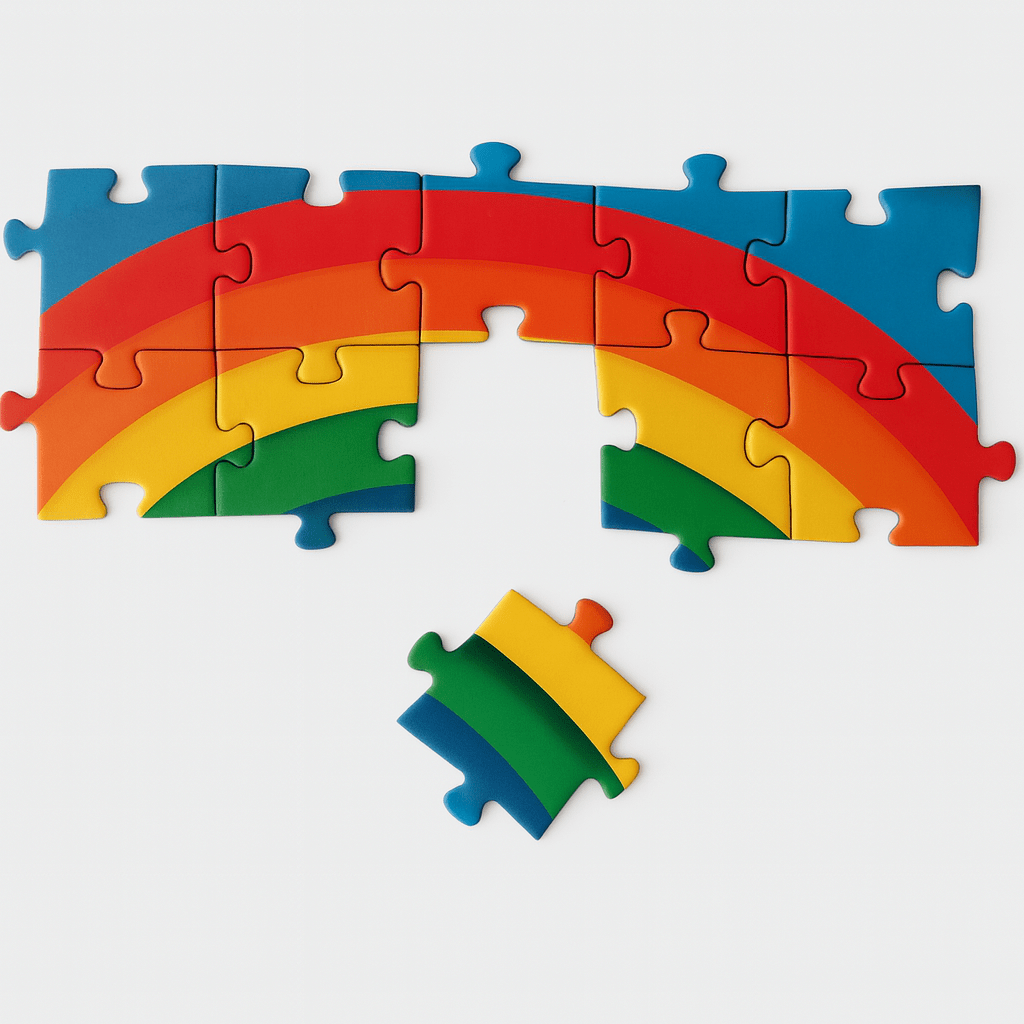

And in the second picture, can we guess that what’s missing is a piece of the rainbow?

Yes — that’s the answer in both cases. So here’s the intuition:

We could collect thousands of such “islands with holes” and train a system to guess what should fill them.

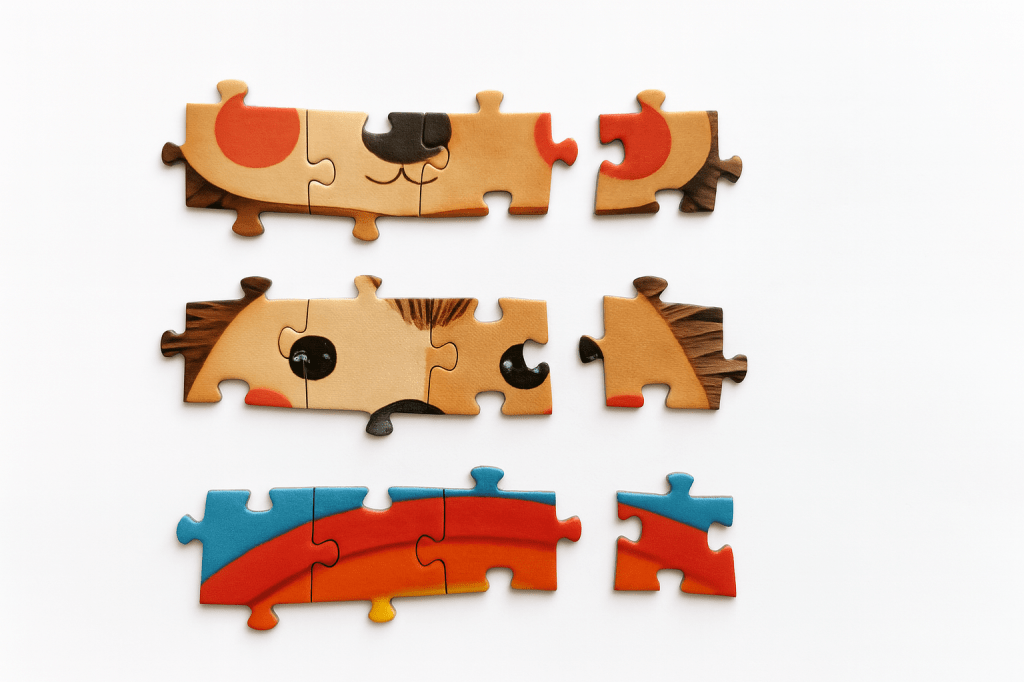

From 2D to Linear: Puzzles in a Row

Now I want to shift to rows of puzzle pieces to make the analogy closer to text, because text is also sequential information. Let’s look at such rows, formed from the same 2D puzzle pieces we used before.

We want to train a system to look at such rows and predict what comes next.

- If we’ve seen a cheek and a nose, the row is likely to continue with another cheek.

- If there was one eye, we probably need to complete the second eye symmetrically.

- If the arc of a rainbow is going up, it’s natural to complete it with a matching downward curve.

The same thing happens with text — we assume that the beginning of a sentence already contains enough information to guess what comes next.

- The hedgehog has one cheek… maybe another? cheek

- The hedgehog has one eye… what’s missing? eye

- The rainbow goes up… and then? down

Our first goal is to understand how we can capture the information from the first three puzzle pieces in a mathematical form so that the model can learn the patterns. This is where attention enters.

Attention = Looking Back to Decide Who Matters

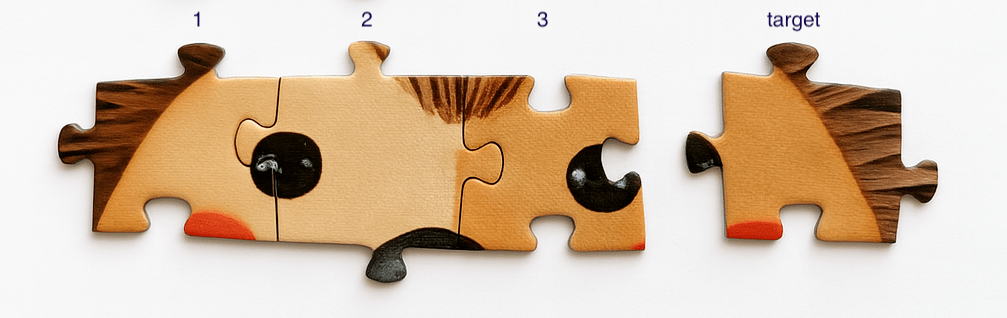

Imagine we want to build a formula that takes three puzzle pieces and predicts the fourth one that fits the row.

To train it, we show many overlapping 4-piece sequences, always masking the last piece and asking the model to guess it. Over time, it learns patterns like:

“On Friday night I usually order…” → pizza, not furniture.

Now look at puzzle 3 — it shows part of a right eye. To understand what should come next, it “looks” at:

- Puzzle 1 — the left cheek

- Puzzle 2 — the left eye

In simple attention, we can multiply puzzle 3 by puzzle 1 and puzzle 2. The result tells us how strongly their patterns match.

Some intuitive examples:

- Left eye ⋅ Right eye → captures symmetry — the network “feels” a mirrored structure

- Cheek ⋅ Eye → low match — those belong to different regions

- Stripe pattern ⋅ matching stripe → confirms continuation of fur

- Blush ⋅ blush → suggests both sides of a face

- Hairline ⋅ darker stripe → weak match — wrong texture

Multiplication reveals when two parts align, repeat, or complete each other. Once we’ve measured how strongly puzzle 3 connects to the previous pieces, we multiply each earlier puzzle by its attention weight — this tells the model which pieces matter more.

But we also care about order. So we add position indices (1, 2, 3), so the model knows it saw eye → nose → eye, not just a mix of those parts.

After we multiply each puzzle piece by its connection strength to the third piece, we perform the final step — we add them all together. This gives us a compressed representation of the context, where both the important details and their order are preserved.

This compressed result is called the context vector. On the left is the context vector needed to predict the puzzle piece on the right.

But real transformers don’t use the raw puzzle pieces themselves in our analogy (or raw word embeddings, which are mathematical representations of words in semantic space). Instead, each word sends a representative to do the job.

- The current token (puzzle) sends a query.

- Each neighbor sends a key (for matching) and a value (the info to borrow).

These Q/K/V vectors are not the same as the raw embedding — they’re linear transformations of it. Each one is computed via a learned single-layer neural net, i.e., a linear layer, no activation.

Let’s now imagine what happens when we transform our puzzle pieces into Q, K, and V vectors. Each transformation gives the same puzzle piece a different role — what it’s looking for, how it describes itself, and what it offers to the final output.

| Puzzle Piece | Q (Query): what am I looking for? | K (Key): how do I describe myself? | V (Value): what do I offer if selected? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eye | Looking for symmetry, a matching eye | I’m a dark round shape | I bring visual focus and gaze |

| Cheek | Looking for a soft curve to continue | I’m pink and round on the left side | I soften the overall shape and add warmth |

| Corner | Looking for a border or edge | I’m straight and light | I signal a frame or outer boundary |

| Fur | Looking for matching texture direction | I’m fuzzy with diagonal lines | I carry continuity and texture |

| Nose | Looking for central alignment and symmetry | I’m centered, small and slightly raised | I bring facial balance and orientation |

This lets the model extract different “views” of the same token. Why? Because the same word might be relevant in different ways. With multiple Q/K/V projections — a.k.a. multi-head attention — we get multiple perspectives at once.

Training the Mappers

We don’t manually program these Q/K/V projections. We just say: “Learn to project embeddings into useful Q/K/V vectors that produce good predictions.” So we train the system by:

- Feeding puzzle rows (or text sequences for real LLM)

- Computing context from attention

- Predicting the next piece

- Comparing prediction to ground truth

- Updating the Q/K/V generators to reduce the error

Do this on millions of examples, and the system becomes able to generalize.

It starts predicting coherent continuations.

Determinism vs Exploration

Once trained, we can use it to predict. We have two main strategies:

- Greedy: pick the highest-probability continuation

- Sampling: allow for some randomness — based on temperature, top-k, etc.

If we think in terms of puzzles: a greedy choice sees an eye and places the matching second eye — a perfect mirror, no doubt. But with sampling, we might try:

- a wink instead of an open eye

- a pirate eye patch covering one side

- a leaf partly covering the eye

Each version still makes sense, but brings a different style or interpretation to the puzzle.

There’s More Inside the Block

Attention alone isn’t enough. Each transformer block also includes:

- Layer normalization (to stabilize training)

- Nonlinearity (e.g., GELU)

- Feedforward layers (to mix and reshape representations)

- Residual connections (to preserve original info)

These elements help the network remain deep and expressive without collapsing.

Stacking Blocks

We don’t use just one transformer block. We stack them. Why? Because deeper layers can refine meaning further. Each layer operates on the output of the previous one — allowing multi-step reasoning. It’s like layering levels of abstraction: from letters → to words → to syntax → to logic → to intention.

Summary

I believe I’ve managed to explain the idea clearly using puzzles — at least the parts without deep learning terminology should feel intuitive.

To write this article, I actually bought a beautiful puzzle and worked through it myself, piece by piece, until I understood how things really fit together.

If you’re curious to dig deeper and get hands-on with how GPT works under the hood, I highly recommend the book by Sebastian Raschka that I mentioned at the beginning. Every great idea has that one click — the moment when a scientist’s brain lights up and thinks, “Wait… this could work.” And I finally understood that click for the transformer.

Leave a comment